Asked about the economists' argument that many more people have been infected than the daily case count reveals, which means that the death rate would be much lower than is being reported, and the suspicion of some that the current method of testing and reporting is making people more afraid of the virus than they really need to be, Beshear did not answer directly.

By Melissa Patrick, Kentucky Health News

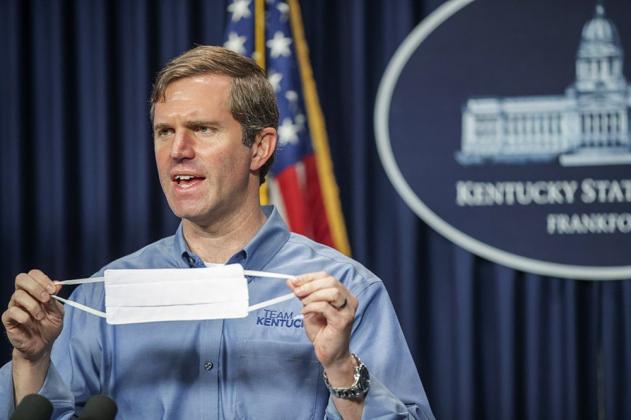

Gov. Andy Beshear disagreed Monday with two prominent Kentucky economists who want the state to do random testing for the novel coronavirus to get a more reliable estimate of its spread than they say is available from voluntary testing.

"My belief is that we have so much testing statewide right now that we are getting an accurate picture," Beshear said at his daily briefing. "I mean, we've got over 2 million, I believe now, total tests that we've done since the beginning of this virus."

He added, "I know some economists, just from a value system, are more worried about, you know, economic impact than lives. But it's not an either-or here. It's not. I mean, all the national economists . . . say that protecting our economy is about lessening the virus, because if people think restrictions are a problem, if the virus continues at this level, anywhere we go in public, anywhere inside, the virus will be spreading and it'll impose capacity restrictions on its own."

The economists are Kenneth Troske, who holds an endowed chair at the University of Kentucky, and Paul Coomes, emeritus professor of economics at University of Louisville. They made their case for increased random testing, combined model-based estimates, in a paper commissioned by UK's Institute for the Study of Free Enterprise.

They write that "convenience samples," as opposed to representative random samples, offer an inaccurate measure of the spread of the disease, and that national studies indicate that as of September, the state was still only identifying one of every two people infected.

A similar result has been found through random testing in Louisville, by the Co-Immunity Project at UofL. Its last round of testing found the number of people who had been infected by the virus was much higher than the number that had been reported.

"We estimate that nearly 34,000 individuals (between 21,470 and 52,900) may have been exposed to the virus – a number much higher than the 17,516 cases reported in the city by the end of September,” Aruni Bhatnagar, director of the U of L Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, said in an October news release.

Asked about the economists' argument that many more people have been infected than the daily case count reveals, which means that the death rate would be much lower than is being reported, and the suspicion of some that the current method of testing and reporting is making people more afraid of the virus than they really need to be, Beshear did not answer directly.

"We're not forcing anybody to get tested, so there's no way to manipulate the numbers to make people more scared," he said. "We've always talked about the death rate probably being lower than what it is right now, but . . . 1,576 people have died, at least in part, due to covid. Again, we can rationalize or create arguments or try to poke holes in the numbers, but is 1,500 people not enough to say it's real. . . . If that economist wants to say, 'See, it's not a big deal,' he can go talk to every single one of those 1,500 families."

Coomes and Troske replied in an email, "The governor has a tough job this year, and he is no doubt doing what he thinks is best for the state. However, our analysis suggests that the state needs more reliable indicators of the spread and lethality of the virus. The state, using results from nonrandom testing, has been grossly underestimating the prevalence of the virus in the population, and thus overestimating the true fatality rate. We believe that more accurate measures would lead to more targeted public-health policies, with no more and perhaps fewer deaths than the state has suffered so far.

"The experiences of the folks running the Co-Immunity project in Jefferson County and the folks from Indiana State Department of Health and the School of Public Health at IUPUI have demonstrated it is possible to successfully conduct testing of randomized populations that produces more accurate data on how covid-19 is spreading throughout a region, which can then lead to a more effective allocation of resources to fight the disease. And while we can’t speak directly for the people involved in the Co-immunity project, we are confident that we all remain willing to devote our expertise in data collection and analysis to help the state implement testing procedures that will produce the data needed to develop these more effective policies."

Business, health and university leaders also seek random testing

The Kentucky Chamber of Commerce, the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky and the presidents of the two universities endorsed the economists' approach in a letter to the governor's office June 17. They called for the expansion of the Co-Immunity Project across the state, using federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act funds.

"This research will provide, for the first time, the real percentage of the population that has been infected, have symptoms and were treated as well as the array of outcomes," the letter said. "The information will be presented by age, gender, race, and location in the community. This data would allow health and policy leaders to determine if the rate of infection is increasing or decreasing, and which parts of the state are most affected.

"Because the same number of tests will be performed each time, the increase in the number of positive tests would not be due to an increase in testing. Such information would help the state catch any resurgence in the rates of infection early before spreading widely and determine whether it would overwhelm the current health care capacity."

The letter notes that the Co-Immunity Project brings together economists from UK and U of L to consider the social and economic impacts of the medical data: "Combining health information with such data as the economic impact of businesses and the characteristics of people who work at or frequent different types of businesses would enable the development of data-driven measures on what types of businesses could safely remain open and what types of workers could continue to work.

"This evidence will support more targeted public health and economic policies as alternatives to broader closing, such as reopening and closing in cycles that may occur until a vaccine or a highly effective treatment is developed. Of greatest importance is the fact that this information would allow Kentucky to effectively protect its most vulnerable citizens in a less costly manner."

Ashli Watts, president of the Chamber, said it still supports this approach. "We still believe that this type of testing could give a more accurate representation of cases across Kentucky," she said in an e-mail. "The experts feel that knowing this data would help as we work to reopen business, schools, etc."

Bonnie Hackbarth, the foundation's vice-president for external affairs, said the foundation continues to support statewide random testing, especially sewage wastewater testing that is also being done by the Co-Immunity Project, because it provides early warning signs of coronavirus hotspots and can guide targeted interventions.

"Regular, random, voluntary testing would give Kentucky the most detailed information about the state of covid at any given time, because it's scientific," she said.

Hackbarth added that the foundation, which focuses on health equity, has invested $50,000 in the project, to not only support its work in Louisville, but to help it expand to Northern Kentucky and Graves County.

"If we can identify hotspots in communities where statistically we've seen that covid rates are higher, so communities of color, lower income," she said, "we can target interventions to reduce the spread in those communities, and start to address the disparities that we're seeing in covid."